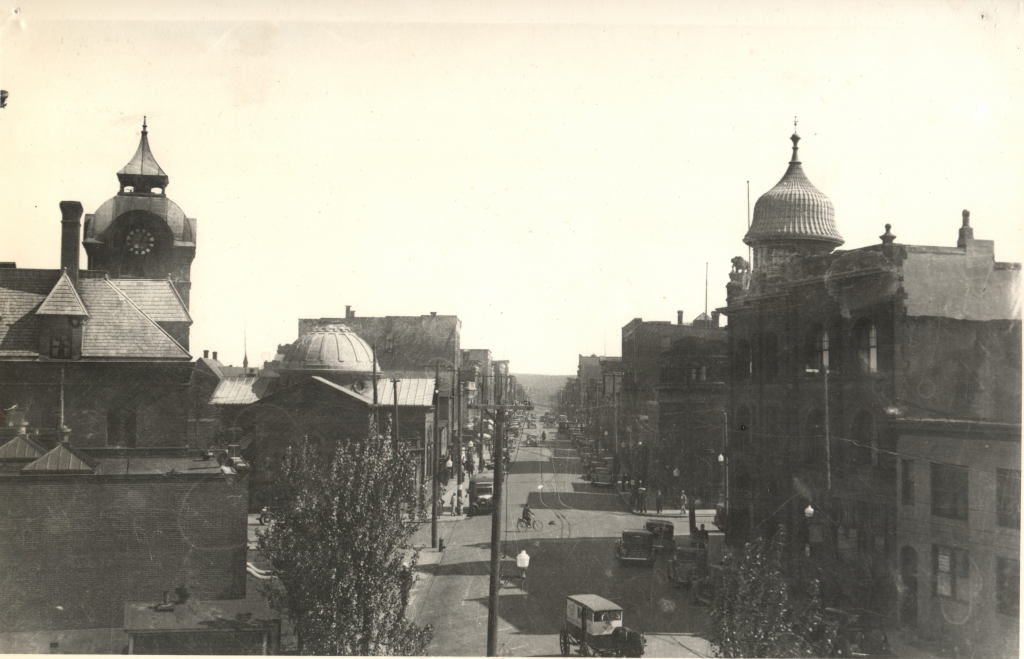

Historic Sydney in 1911

When Charles Freeman and his family arrived in Sydney, Nova Scotia on November 19, 1911, the city was already an established industrial port that had undergone a period of dramatic change in the early years of the twentieth century. Until 1820, Cape Breton was a separate colony and Sydney was its capital. Even after annexation to Nova Scotia, the city still possessed the air of a small colonial garrison town with a military presence until 1854. Its society was made up of elite retired military officers, office holders, and a small professional class. Sitting at the head of the harbor, it was the largest town and focal point of the district. The area was rich in coal. After the introduction of the railway in the late nineteenth century, Sydney became an important port for the shipping of coal.

With the construction of the steel plant in 1899, Sydney grew quickly. People came from all over the world to meet the demand for workers at the plant and still that was not enough. Active recruitment brought workers from Italy, Eastern Europe and the Caribbean, with many establishing communities in Sydney’s Whitney Pier area that still exist to this day. From 1899 to 1901 Sydney’s population tripled from 3000 to 9000 and in 1904 Sydney became incorporated as a city.

By 1911, Sydney was home to one of the largest steel plants in the world that was fed by the coal mines in the area, all under the ownership of the powerful Dominion Steel and Coal Corporation (DOSCO). The city’s economy was significant to Industrial Cape Breton due to its steel plant, harbor and railway lines that connected the coal mining towns of Glace Bay, New Waterford, Sydney Mines, and Reserve Mines.

Social Structure

The influx of new people had a dramatic effect on Sydney’s social structure in the first decade of the twentieth century. The old colonial mentality was all but shattered, and the class structure became fragmented. Steel plant officials built grand homes in the suburbs along Kings Road and on the south end of Park Street and Whitney Avenue. Other professionals such as bank directors settled away from the steel plant in the Sherwood area in the south of the city. The old elite living in Sydney’s North End could not compete with all this wealth and privilege. While some members of the former elite attempted to establish a “Boys of Old Sydney Club,” it did not last. Some did mingle socially with the new arrivals, but generally, owners of the steel and coal industries did not become part of local society.

As was common for women of the time, the wives of the industrialists and those connected to them lived a life of teas, garden parties, and painting. Charles Freeman’s wife, Susan, socialized with women of this group. In this period, Petersfield, built by industrialist J.S. McLennan in Westmount on Sydney Harbour, became the place to go for those who visited Sydney. When the Freeman family arrived in Sydney, they often picnicked at the estate during the summer months.

In addition to Sydney’s elite, there was a new level of society unknown before the steel boom. Within this group were the support staff for the plant, including secretaries, accountants, chemists, and superintendents. This group was made up of a mixture of Cape Bretoners and new arrivals, often from other parts of the Maritime Provinces. They lived in modest homes in the newly developed Ashby area and the old Shipyard area of Sydney.

Finally, there was the laboring class which represented the majority of Sydney’s population. They tended to live near the steel plant, mostly in Whitney Pier, which consisted of several different communities divided along ethnic lines, the legacies of which can still be seen throughout Whitney Pier today.